Open Source, Enterprise-level Data Pipeline

Posted on 10 Jun 2022 by Pavan Behara

In this blogpost I would like to introduce you to our molecular dataset generation workflow. At Open Force Field, we generate a lot of Quantum Mechanics (QM) data as well as Molecular Mechanics (MM) data, predominantly for drug-like small molecules. A few data oriented tasks include:

- training the valence parameters in the force field

- benchmarking the force field

- building bespoke parameters based on fragment torsions

- building machine learning models to predict charges

- building machine learned potentials

and many more analyses to answer scientific questions related to virtual sites, polarizability, etc.

In the context of openforcefield work, datasets can be broadly classified into three calculation types:

- Single point energies, with or without hessians (termed as BasicDataset)

- Optimized geometries of conformers (OptimizationDataset)

- 1D and 2D torsion potential scans (TorsionDriveDataset)

The QC* suite of python packages (QCElemental, QCEngine, QCFractal, QCPortal, QCSchema), from our peers at the Molecular Software Sciences Institute (MolSSI), as well as openff-qcsubmit from our stable, are the foundation on which our data infrastructure stands.

The qca-dataset-submission repo, spearheaded by David Dotson and team, is our Github-based data pipeline with automated features for input validation, job submission, job monitoring and error cycling.

It is a culmination of years of effort into standardizing and simplifying the process and knitting together lot of packages to work in harmony in production environments.

QC* packages are used for various purposes; for example, QCSchema is the standard we use to specify our calculation’s common quantum chemistry method.

QCFractal is the job submission and queue management package, which uses QCEngine as the underlying interface to various QM and MM packages.

Psi4, a widely used, community-driven, highly efficient open source electronic structure code, is the workhorse for our QM data generation.

QCEngine supports a lot of other electronic structure packages (GAMESS, NWChem, etc.), analytical corrections (DFTD, gCP), semiempirical methods (XTB, Mopac), MM and AI potentials (GAFF, openforcefields, ANI) as well.

The long list of supported programs can be found in the QCEngine documentation.

The data generated with the help of these software tools is hosted on a public repository, known as Quantum Chemistry Archive (QCArchive).

This resource is managed and further developed by Benjamin Pritchard from MolSSI, to whom we owe many thanks in enabling the work we do with this resource.

Much software development effort has gone into streamlining and automating most of the tasks, which can be broadly classified as:

- Dataset preparation

- Setup server and compute on an HPC cluster

- Data access post-computation

Dataset preparation

The first step involves creating a set of molecules you want to generate data on. You can use any of the available cheminformatics packages, and the input can be either 3D geometries in SDF format, or simple text based 2D representations such as SMILES. Our datasets adhere to an evolving protocol of standards created by Trevor Gokey (https://github.com/openforcefield/qca-dataset-submission/blob/master/STANDARDS.md), keeping in mind the needs of training data for fitting. We started with a compute-every-property approach when resources were abundant, but noticed the rising burden on storage infrastructure which made us move to a compute-and-store-necessary-properties policy. As an example, if we store the bond indices on a million molecules dataset where we intend to use only energies and forces this would occupy 100s of gigabytes of QCArchive storage with data that will never be used. Such choices on property calculations have to be evaluated in advance so as to avoid choking up the server infrastructure. After those initial decisions, openff-qcsubmit, developed by Josh Horton and team, can ingest the molecules’ information, quantum chemistry specification, additional metadata, and create dataset blobs that serve as input to QCFractal. In our pipeline these submissions are merged after a pull request (PR) has been made and reviewed, but it is not necessary for other users in practice. We use Github Actions to validate a dataset and catch any mistakes that had slid during the preparation stage. This automated step alleviates human error both in preparation and PR review.

Computation on an HPC cluster

We utilize spare resources across multiple compute clusters to process our QM workloads for fitting datasets. We submit job managers using the cluster management backend, e.g. SLURM, PBS, or Kubernetes, and these managers reach out to QCArchive for work to execute. We sincerely thank the patience of our HPC admins on the following clusters for allowing us to use as many idle resources as possible on top of our paid usage:

- HPC3 and Greenplanet clusters at UCI

- Lilac cluster at MSKCC

- TSCC at UCSD

- Pacific research platform (PRP)

- Sherlock at Stanford

- GWDG at MPI Gottingen

and also we thank our superusers who set up and monitor the job managers from time to time.

Job managers can be spun up with different node configurations (cores/memory) depending on the program specification and system size.

For example, a CCSD(T) calculation needs more resources than a hybrid DFT calculation.

One caveat of using academic clusters is that we have to run a lot of jobs on pre-emptible queues to make use of idle nodes, thus when a job is suddenly stopped it returns an errored state.

We have built an errorcycling script set up on our qca-dataset-submission Github Actions that periodically goes through each dataset under compute and restarts those failed calculations.

This bot prints relevant error codes for the failed runs and it would help in debugging persistent issues.

After the dataset finishes all calculations it is archived automatically. Some datasets never achieve 100% completion but instead attain an acceptable error state (say 99% complete), and a decision is made to move it to end-of-life manually after reviewing the remaining errors. Some of these error handling tasks may be incorporated into the next release of QCFractal and performed server-side on QCArchive, reducing the burden on downstream users.

As of now QCArchive stands at 98+ million molecules, 104+ million different calculations, and 207+ dataset collections. This is a testament to how open source science can help in creating standards and generating an immense amount of data for everyone to access and work with.

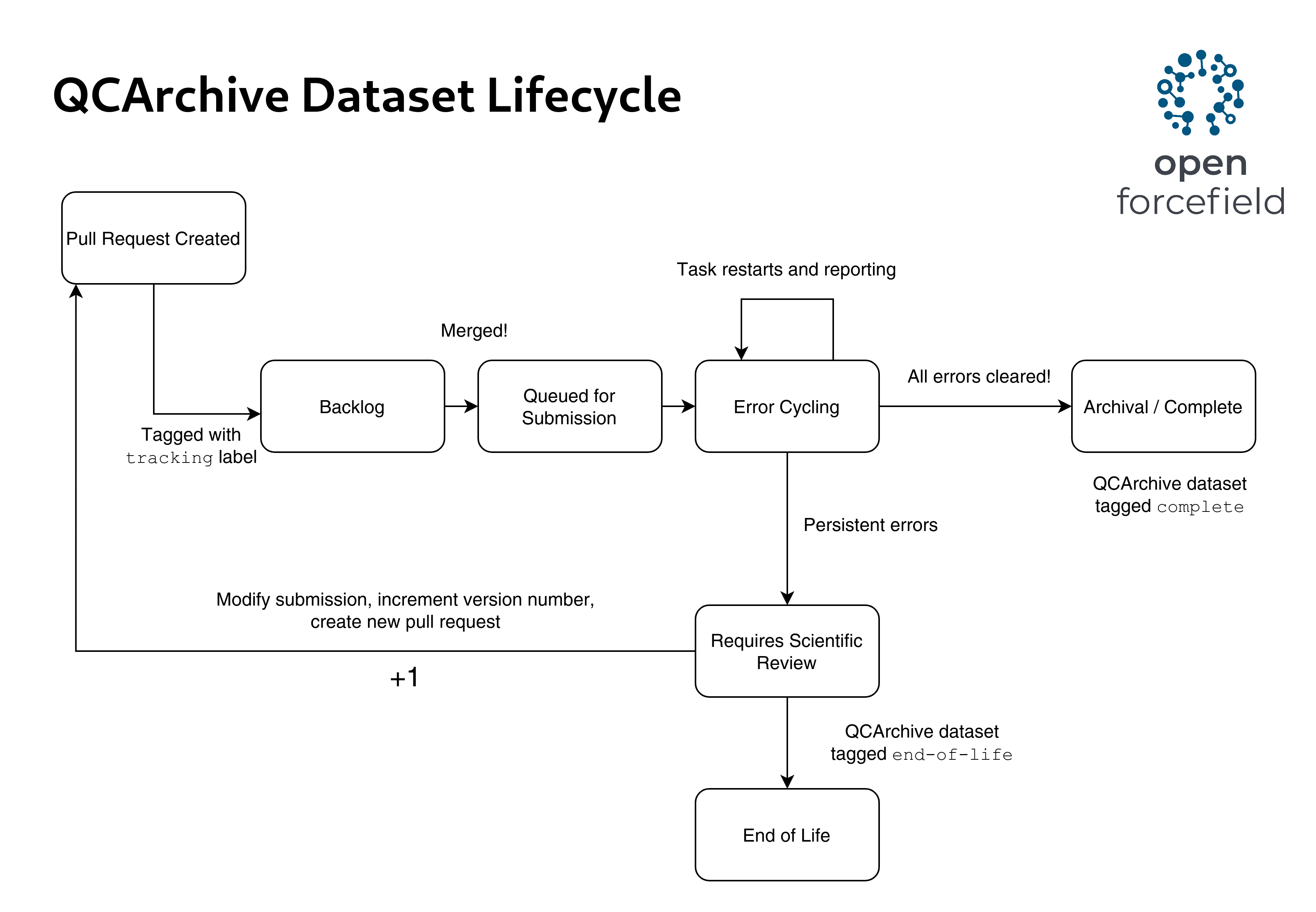

A dataset lifecycle is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: David Dotson’s illustration of a dataset’s lifecycle

Data retrieval

Dataset retrieval is again facilitated by openff-qcsubmit and there are a lot of post-processing functions that help filter out the necessary molecule sets. Single point calculations are still a little bit difficult to download; faster and evolving infrastructure changes aim to smooth it further.

A working example of creating a torsiondrive dataset of biaryls with different substituents is shown in the notebooks for anyone interested. Setting up a manager and worker on a slurm based cluster is also given in the notebooks.

Evolving infrastructure

As we use our existing infrastructure, we are always looking for ways to improve and evolve it. QCArchive is a key component of our forcefield-development pipeline, and our use has driven improvements to the QCFractal codebase that powers it. We hope to soon share upcoming improvements in a future post in the coming months once they are deployed and in use.